Malaysia Project (Cinema)

Background and Objectives

It would probably not be wrong to say that Japanese cinema of recent years has received a decent level of international critical acclaim, given the number of films that have been honored with nominations and awards at international film festivals. This acclaim may be attributed to the historical fact that Japan’s film industry inherited cinematic expression techniques from the Studio era, which is now commonly considered to be the Golden era of cinema with masterpieces from internationally acclaimed filmmakers including Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu, and then proactively applied advanced digital technologies to film production. This approach took advantage of Japan’s status as an international leader in the area of digital technology. The Graduate School of Film and New Media (GSFNM) at Tokyo University of the Arts (TUA) was established in 2004 in the midst of the transition from film to digital production, and the school is noteworthy as the first full-fledged cinema education and research center within a national university in Japan. Over the last few years, the Graduate School of Film and New Media has undertaken research projects on film education systems based on new types of film production that are suited to the digitalized cinema environment. Completed in 2016, The Manual for the Education of the Digital Cinema Production Workflow is one of the outcomes of this research. The Digital Cinema Production Workshop is the first program to utilize this educational manual.

The cinema of Malaysia, the host country of this program, remains relatively unknown on the international scene, with the exception of a handful of world-famous filmmakers such as Ming-liang Tsau. It may well be said that Malaysian cinema is still at the developing stage. However, the situation is changing, as Malaysian cinema is achieving greater prominence in Asia. For example, the entertainment industry is featured in the Malaysian government’s large-scale Iskandar urban development plan in the Johor region, and Iskandar is home to Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios (PIMS), one of the largest media production studios in Asia. In addition, international co-productions are given preferential treatment for government subsidies. Another characteristic of Malaysian cinema that deserves special mention is that the language barrier, the toughest obstacle to be overcome when it comes to the world market, is relatively low in this country, where a wide variety of languages including Malay, English, and Chinese are spoken. Malaysia’s geographic proximity to Singapore, one of the economic giants in Asia, is also important. Malaysia’s motion picture culture and cinema industry clearly have plenty of potential, given the lively economic, cultural and social exchanges already taking place. Collaborations between Malaysia and Japan have already begun at the industry level. Several years ago, IMAGICA, a major post-production house in Japan, made its way into PIMS and established a local company called IMAGICA South East Asia (ISEA). This company is actively involved in developing local human resources and has played a central role in enabling us to hold workshops at PIMS for this project for two years.

This Digital Cinema Production Workshop is based on the digital cinema education manual created by Tokyo University of the Arts and aims to harness the unrealized potential of expression through motion picture techniques and cinematic creativity with digital cinema production in an optimal environment equipped with large-scale studios and cutting-edge post-production facilities. The workshop aims to enable young people in Malaysia and Singapore to deepen their understanding of Japanese culture and experience first-hand the techniques and thought processes used in cinema production, as well as the passion involved. Participants are under the guidance of a director, director of photography, production designer, and editor, all of whom are among the best in Japan. The workshop’s final outcome is the production of four short pieces, each about ten minutes long.

Team

| From Japan | |

|---|---|

| Instructors | Nobuhiro Suwa (Filmmaker/Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) |

| atsumi Yanagijima (Director of Photography/Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) | |

| Toshihiro Isomi (Production Designer/Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) | |

| Ryuji Miyajima (Editor/Part-time Instructor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) | |

| Assistant Instructors | Mami Morisaki (Assistant Camera) |

| Keisuke Ikeda (Assistant Gaffer) | |

| Yusuke Yamada (Assistant Editor) | |

| Director | Shogo Yokoyama (Specially appointed assistant professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) |

| Assistant Director | Issei Matsui (Freelancer) |

| Project Producer | Mitsuko Okamoto (Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) |

| Translators | Asako Eguchi (Specially appointed assistant professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts) |

| Planning and Administration | The Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts |

| General Management | UNIJAPAN |

| Project Chief | Takenari Maeda (Group Manager, International Promotion Group) |

| Project Administrator | Mayu Honda (International Promotion Group) |

| From Malaysia | |

|---|---|

| Local Coordinator | IMAGICA South East Asia (Supervisor: Kentaro Kusaka) |

| Naoki Tanaka (Post-production Supervisor/Interpreter) | |

| Izmil Idris (Production Department) | |

| Shinichiro Muraoka (Production Department Assistant) | |

| Special Instructors | Kenichi Fujimoto (Production Sound Mixer) |

| Hiroyuki Ishizaka (Sound Designer) | |

| Participating Educational Institution | Multimedia University |

| Supporting Organizations | Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios(PIMS) |

| Red Circle Projects | |

| From Singapore | |

|---|---|

| From Singapore | Hideho Urata (Director of Photography/Professor at LASALLE College of the Arts) |

| Participating Educational Institution | LASALLE College of the Arts |

Instructor Profiles

-

Nobuhiro Suwa (Filmmaker/Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts)

-

Katsumi Yanagijima (Director of Photography/Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts)

-

Toshihiro Isomi (Production Designer/Professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts)

-

Ryuji Miyajima (Editor/Part-time Instructor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts)

-

Hideho Urata (Director of Photography/Professor at LASALLE College of the Arts)

-

Kenichi Fujimoto (Production Sound Mixer)

-

Hiroyuki Ishizaka (Sound Designer)

Project Overview

《Project Name》

“Digital Cinema Production Workshop in Malaysia”

《Dates》

October 31 to November 5, 2016

《Venues》

Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios (PIMS)

- Fillm Studio3

- The premises of PIMS (location shooting)

- IMAGICA South East Asia (post-production work)

- VIP Room (screenings and discussions)

《Participants》

Participants: 26 students

Students’ University Affiliation:

Multimedia University (15 students)

LASALLE College of the Arts (6 students)

Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School of Film and New Media, Department of Film Production (5 students)

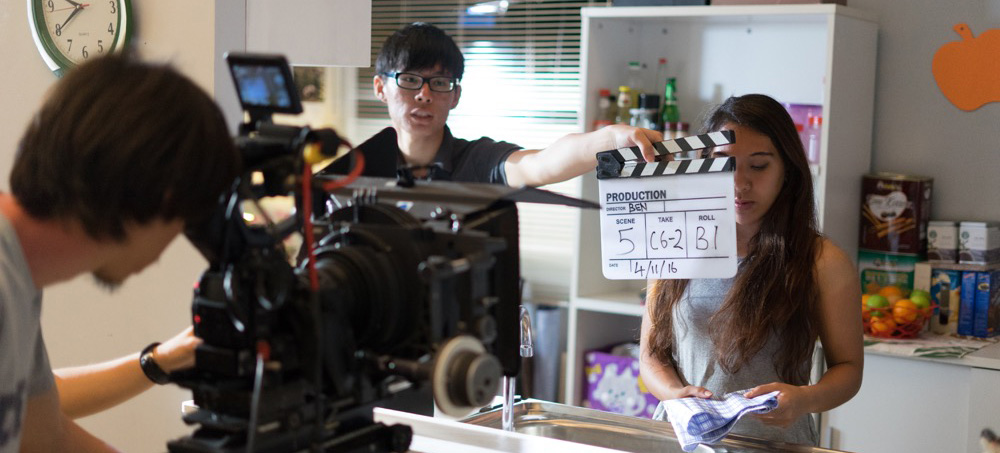

Details of the Workshop

Participants were given an orientation at the beginning of the workshop. They were introduced to the workshop instructors and to each other, and they were given an explanation of the intent and contents of the workshop, as well as the schedule. The participants were divided into groups in Film Studio 3. The organizers had divided the 26 students into four groups of six (Groups A to D) and a group of two (art department) on the basis of the information provided beforehand. When participants shot their films, Groups A and B formed a single team, and Groups C and D formed another team. The same actors were shared by both teams. When one group in a team shot, the other group in the same team would take on a supporting role, and vice versa, so that the groups in the same team would help each other.

<<Digital Cinema Production Workflow Guidelines>>

In the second half of the orientation, director Yokoyama explained the Agile production system*3 as described in the “Digital Cinema Production Workflow Guidelines,” which was used in the workshop. More specifically, he explained the “dialogue” that was key to the workshop, as well as the method and expected outcomes.

<<Restrictions on shooting techniques>>

n this workshop, certain restrictions proposed by the cinematography instructor were imposed on the shooting techniques. The participants had to abide by the following three restrictions during their shoots.

1) Only 35-mm lenses were allowed on the cameras.

2) Shoot only in black & white.

3) Camera monitors cannot be used.

The purpose of these restrictions was to give the participants an environment in which they were encouraged to actively figure out what sort of cinematic expression was possible within the limits imposed on their shooting methods. The participants were required to think about the characteristics and coverage of the 35-mm lens and how to cinematically express light in black & white. In addition, they experienced a film shoot in which they could not check their shot footage using camera monitors.

<<Pre-production>>

In the second half of the orientation, the participants split into their assigned groups. The groups discussed what role each person would play in the production process and how the film shoot would proceed. The main roles to be fulfilled in the workshop were director, cinematographer, gaffer, editor, sound recordist, and assistant director. If preferred, we made it possible for them to change roles from one scene to another without fixing one person to one role. We let each group take its own initiative in pre-production. We let each group discuss the screenplay and freely make its own schedule, including storyboard creation, location scouting, rehearsal with the actors, etc. We also set aside some time for the assistants to explain how to use the equipment in the workshop, mainly for those interested in entering camera or editing departments.

《Days 2 to 6: Shooting and Editing》

From Day 2 to Day 6, each group worked on the production of a short film following the schedule prepared by the organizers (see attached schedule). The film production in this workshop followed the Agile production system in which shooting and editing progress simultaneously. When they shot, one group in a team acted as the main unit and the other as the second unit, and they took turns at preset intervals. Data was passed from the camera unit to the editing unit after each scene was shot. We instructed them to appoint a person in each group to be responsible for data exchange, so as to prevent data loss. The workshop participants managed aspects of the shoot, including the wardrobe for the actors, notifications to the actors for their appearances, and the handling of props. The organizers took charge of schedule management during the shooting. The organizers requested the instructors for camera/lighting and directing to just watch the shoots and refrain as much as possible from giving specific instructions on set.

<<On-set shooting>>

The sets were constructed in advance based on plans prepared by the organizers. Basic lights for the sets had been rigged in advance under the guidance of the camera/lighting instructors. The participants were encouraged to create such lighting as relevant to the intention of each scene based on these basic lights. Some of the walls in the sets were removable, giving more flexibility for camera positions on the set and allowing the participants to experience the shooting method that is only possible on a set. The furniture on the set was provided by the organizers, and each group freely gathered the props they needed. Those in the art department consulted the director of each group and others and kept track of the positions etc. of the props. For the shoots on the constructed sets, production design instructor Isomi taught all of the students (not just those in charge of art) about the ideas underlying on-set shooting, including how to move the sets and prepare and arrange props. Scenes 2, 3 and 5 were shot on set. In order to allow the participants to experience different light settings (for day and for night), Scene 2 was set at night, and Scenes 3 and 5 were set during the day, on the advice of the camera/lighting instructor. The students basically took the initiative during the on-set shooting, with the lighting assistant and others helping and advising them mainly about how to set lights.

<<Location shooting (mangrove forest / café)>>

Two types of locations were used. One scene took place in a mangrove forest, another at a café. We used the mangrove forest near PIMS for the mangrove forest scene. The students were allowed to shoot anywhere in the forest as long as they remained within walking distance. Scenes 1 and 6 took place in a mangrove forest, and, given the nature of the story, the use of a smoke machine was allowed as a directorial device. For the café, which was the location for Scene 4, the balcony of the café on the premises of PIMS was used. The students were allowed to rearrange the tables and the chairs at the café. Only minimal lighting equipment consisting of reflectors and such was allowed on location in order to have the students focus primarily on camera positions and camera operations. We asked the camera assistants to assist and instruct the students with these intentions of the workshop in mind.

<<Editing>>

Those who were assigned to editing carried on the editorial work as they received the shot footage. Meanwhile, the shooting was still underway. The editing instructor checked what the students had edited together only after a scene was largely complete. The editing instructor and his assistant gave the students advice on visual expression and technical assistance, rather than telling them specifically how to edit. We created an environment in which the editing instructor could give the editing students more practical advice by having him check the dailies and share the intentions of each editor. We used ISEA’s post-production facilities as editing rooms, and an editing room was allocated to each group. The ISEA staff was in charge of technical support. We did not set aside time for sound mixing and grading in this workshop. For grading, we only allowed the adjustment of contrast and brightness to the extent that it could be accomplished within the allocated time in the joint opinion of the cinematographer and the editor. We also instructed each editor to mix the sound to the best of his or her ability.

At the end of each shooting day, each group’s members gathered in their own editing room. They had a screening of what had been edited together and shared the status of the production in progress. The editors presented the intentions of the edit, the problems found in the piece at that point, etc. before they showed the dailies. We set aside some time for them to talk about how the scenes to be shot next should be directed and shot, how to solve the problems at hand, etc. on the basis of the current edit, without ruling out a potential reshoot. Sharing at this stage knowledge about cinema production among the crew members was essential. The last day was entirely devoted to editing, with no shooting allowed. The editing students were instructed to have asked the opinions of the director and the other crew members by then so as to make the final editorial decisions and take responsibility for the finished work.

<<Dailies and editorial review sessions>>

Before roughly assembled dailies were screened at the end of each shooting day, each group had a session in which the dailies of the day were reviewed by the cinematography instructor and others. While viewing the footage actually shot by the students, each instructor gave them feedback on where the intended cinematic expression succeeded or failed, where cinematographic skills needed improvement, what alternative approaches could have been taken, and so on. The purpose of this approach was to give the participants an opportunity to think about why they had made mistakes. In order to accomplish this goal, the instructors were not allowed to intervene in the students’actual shooting, and instead specifically pointed out the failings in the footage after that day’s shooting was complete. In particular, the instructors repeatedly urged the students to think through the cinematic implications of using only 35-mm lenses and black & white, the two restrictions imposed on them for this workshop. The students were able to gain more profound knowledge about expression through cinematographic techniques by sharing knowledge about film production among themselves, and also having their skills reviewed in concrete terms by the instructors.

<<Final screening and review session>>

We used the VIP room at PIMS for the review session of the finished pieces. The screening was held in alphabetical order, starting from Group A, followed by Groups B, C and D. Each group member announced his or her role in the crew before the screening. After all the pieces were screened, all the instructors reviewed them. Each instructor gave very attentive comments, covering not only the technical aspects of the pieces’visual expression but also each group’s approach to film production, including its collaboration scheme and the quality of its internal communication. Afterwards, the instructors voted for the best piece award. A party was held after the review session in which students actively asked questions to the instructors and engaged in discussions about film production and specific films. At the end of the party, project director Yokoyama announced the winner of the best piece award and the students in Group C received commemorative gifts. We thanked the local staff and actors who helped us bring the workshop to fruition. Thus, the entire program came to an end.

Conclusions

Many of the participants in this program not only realized the difficulty of making a film with a multi-cultural, multi-language crew but also the importance of communication in film production. The Agile production system of the digital cinema production workflow adopted for this workshop enabled collaborative learning for the participants, who engaged in “dialogue” as they shared tacit knowledge about cinema and film production. Participants had much to learn from each other, despite differences in skill level and film production experience. After the rough-cut screenings, group members expressed their opinions about the issues confronting their work-in-progress films and discussed solutions from the viewpoints of both editing and cinematography. Participants expressed their own opinions and were able to get first-hand exposure to various types of knowledge and ideas. These discussions were very important for them. One example of the kind of differences that arose from diverse lifestyles was how to design the lights indoors. During the workshop, it became evident that people in Singapore and Japan think differently about how bright it should be indoors at night. This is due to the fact that buildings are closer together in Singapore, with lots of light pouring in from the outside at night, while indoor lights are brighter than outdoor lights in Japan. This difference helped the participants realize that there were markedly different ways of expressing the night light and taught not only the participants but also the instructors the importance of rethinking assumptions in different situations. This difference went beyond mere “circumstances” and triggered the participants to think about how such differences affect their approaches to cinematic expression and storytelling.

The results of the questionnaire suggest that many of the MMU students felt that they lagged behind the others in terms of techniques and cinematic knowledge. It is very significant that the MMU students felt that way. Indeed, they lagged behind the students from the other two schools in terms of technical knowledge. We hope that this awareness gained through the workshop collaboration will result in increased commitment to film production in the future. On the other hand, we feel that most of the LCA students were able to acquire shooting techniques and knowledge about the equipment. We must say that the mandatory use of a specific lens and black & white pictures and the prohibition of using monitors, suggested by the instructor for cinematography, was very beneficial. The participants from Singapore had already a certain amount of cinematographic skill and knowledge, and the restrictions in effect challenged them to achieve a higher level of knowledge and insight about lenses and light.

In addition, the review of dailies conducted by the instructors at the end of each shooting day was very effective from an educational viewpoint. The instructors deliberately focused on where the cinematic expression failed rather than succeeded, which made the students search for the reasons and plan for better execution, thus resulting in creative and technical improvements for the next shooting day. The instructors were amazed by the students’ technical and creative progress each day.

Although the questionnaire responses indicate that the workshop was highly effective in terms of acquiring cinematic knowledge and techniques, there are points that can be improved in order to hone future workshops. The editing instructor pointed out that there was too little time allocated to editing. The limited editing time impacted the quality of the finished pieces, and also meant that there was insufficient time for “dialogue,” which was essential for the workshop. The participants cannot be blamed if they place more emphasis on finishing the pieces than on having better “dialogue,” but it is necessary from an educational viewpoint to make more time for all of the crew members to gather and engage in “dialogue.” Thus, it is important to set aside enough time for editing in future workshops. Looking back at the whole post-production stage, the time allocated not only to editing but also to sound mixing and to fine-tuning the picture such as by grading was quite limited as well. If we think about the quality of the produced works, we may have to reconsider the allocation of time for each step in production. However, the organizers need to make clear whether the workshop prioritizes the production of works or the educational aspects, and must construct a production schedule that is appropriate for the objectives.

For this workshop, the organizers had prepared a screenplay consisting of six scenes. Some instructors were of the opinion that a shorter screenplay might have resulted in less pressure on set. We would like to come up with a more appropriate volume for the screenplay which will encourage enhanced “dialogue” and afford sufficient time for editing and creativity on set.

There were also issues regarding crew assignment within each group. For example, some students were not assigned to the position they wanted and consequently lost motivation. In other cases, the technical inadequacy of those who were assigned to unfamiliar positions adversely affected the quality of the finished piece. For this workshop, we grouped the participants on the basis of the information provided beforehand, and let them assign crew positions on their own. However, if we consider the participants’ motivation and reasons for participation, it is true that we will probably have better workshops by intervening in crew assignment as well. We plan to work out these issues and shortcomings that have been pointed out.

The students gained invaluable experience through shooting their films at PIMS, which is among the best and largest film studios in Asia. More importantly, it is highly unusual to have a workshop of this length that brings together so many top-notch working instructors and have them offer their expertise on film production to students. Many of the participants took full advantage of this opportunity to discuss film production with some of Japan’s best filmmakers and actively asked them questions not only about techniques but also the Japanese cinema. They listened wholeheartedly to the Japanese instructors, reflecting their earnest attitude towards filmmaking. The participants also interacted actively with one another, and some of them spent time together after the workshop. On set, they gave each other advice on shooting techniques and how to use the equipment.

The quality of the four finished pieces exceeded the expectations of the staff and instructors. Even given the restricted schedule and shooting environment, the participants made remarkable progress on a daily basis and their industrious and earnest attitudes deeply impressed the instructors.

Many of the workshop participants told us that this program was a very positive experience. The workshop’s success is due entirely to the passion and dedication on the part of the Malaysian staff, as well as the instructors including Mr. Suwa, Mr. Yanagijima, Mr. Urata, Mr. Isomi, Mr. Miyajima, Mr. Fujimoto, and Mr. Ishizaka, who took precious time from their busy schedules to participate in the workshop. We would like to take this opportunity to once again express our deep gratitude to the staff and instructors who made this workshop a success.